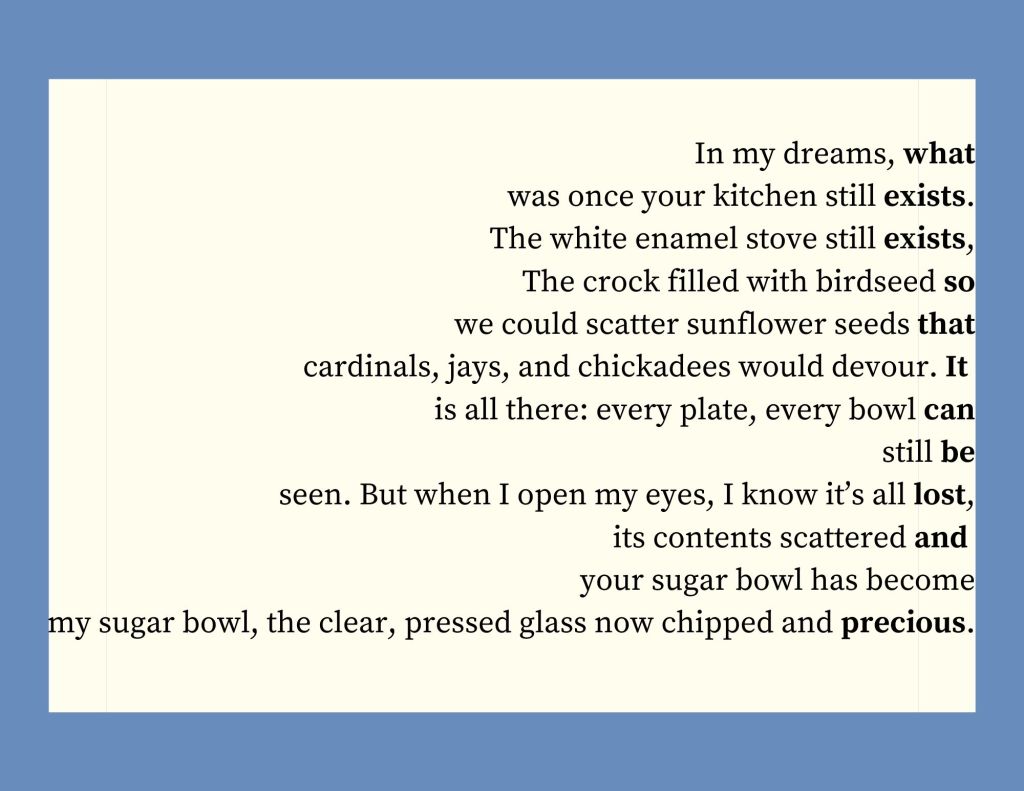

It’s been an interesting week and I don’t really have a good excuse not to have written a poem earlier. Still, here we are on Friday morning and I’m just pulling this together, so please be patient with my very drafty last minute Poetry Friday offering. I found the strike line for this Golden Shovel in The Birmingham Arts Journal, Vol. 17, Issue 2.

“Every one of us is an artist by default, reinventing the world each time we remember something.”

Ben Brantley

Each and every

day, I have at least one

thought that wants to become a poem. Of

course, only a small fraction of them actually make the journey from pen to page. Experts tell us

to write every day, that this is

the only way to hone our craft, to become an

artist.

But I’m not sure. By

letting ideas simmer on a default

setting deep in my brain, ideas are morphing, reinventing

themselves into something new. When the

time is right, they will alert me they’re ready to go out into the world.

I give each

possibility the time

it deserves. Some are compliant and yielding; others kick my butt. Yet we

always arrive at a solution that pleases us both. Whatever the outcome, I have to remember

this process always teaches me something.

Draft © Catherine Flynn, 2022

Please be sure to visit Laura Purdie Salas for the Poetry Friday Roundup.