Last week was filled with family, friends, and, dare I say it, work. So instead of 10 picture books, here are 12 of my favorites.

Picture books have been at the heart of my teaching for the past 17 years. Wordless picture books are particular favorites and I love teaching with them. They are perfect for improving students’ comprehension, writing, and visual literacy skills.

Wordless picture books can be used to support comprehension strategies in all readers, but can be especially useful with young readers as well as older struggling readers. Removing the challenge of decoding allows students to focus all their attention on understanding. They are a perfect scaffold, as they give students an opportunity to understand how to use a strategy to make meaning, then learn how to apply that strategy with print. Wordless picture books can also be used to address CCSS Anchor Standard 7: “Integrate and evaluate content presented in diverse media and formats, including visually and quantitatively, as well as in words.”

Not only do wordless picture books support comprehension development, they offer numerous writing possibilities. Narrative structure, dialogue, and use of details are just a few of the many writing skills that can be addressed through wordless picture books. The humor in many of these titles make them especially appealing to reluctant writers.

Some author/illustrators stand out in the wordless picture book genre. David Wiesner is my favorite, and most teachers are probably familiar with his work.

Tuesday, the 1991 Caldecott Medal winner, is a classic. Students love the humor this book, as well as the mystery of the airborne lily pads.

Flotsam, which won the 2007 Caldecott Medal, is a bit more mysterious and is better suited for older readers. They enjoy puzzling over the lush illustrations and discovering the endless creativity of David Wiesner’s imagination.

Emily Arnold McCully’s Picnic and First Snow (other titles featuring this family are School and New Baby) are well suited to the youngest readers. Featuring an endearing family of mice, these books chronicle their adventures through the eyes of the youngest sister. Identifiable by her pink hat or stuffed mouse, Kindergarten and first graders will identify with her immediately. Brief text was added in 2003, and although I have not used these versions with students, I prefer the wordless versions. These can sometimes be found at Powell’s, Better World Books or Alibris.

Be sure to read Pancakes for Breakfast, by Tomi dePaola, early in the day before everyone gets hungry. Or better yet, share the story, then make pancakes! The clear sequence in this book make it a perfect choice for writing an interactive how-to book.

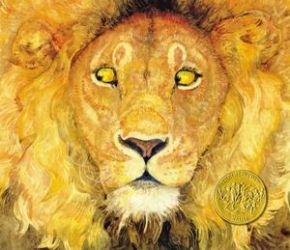

Jerry Pinkney’s The Lion and the Mouse, winner of the 2010 Caldecott Medal, is a lush retelling of a timeless tale.

Good Dog, Carl by Alexandra Day. Dogs as babysitters are not new to children’s lit, but Carl is one of the most mischievous and lovable.

Mercer Mayer’s A Boy, a Dog, and a Frog is filled with the kind of adventures I loved as a kid. Perfectly sized for little hands, this book is the first in a series of the characters’ continuing escapades.

Sidewalk Circus by Paul Fleishman, illustrated by Kevin Hawkes is a very clever look at how, with a little imagination, everyday scenes can evoke completely different situations.

Good Night, Gorilla, by Peggy Rathmann is a mostly wordless gem. Students find great delight on being “in”on the fact that the animals are climbing out of their cages as soon as the zookeeper says goodnight. It just occurred to me that this may be a good text to introduce dramatic irony to older students. Again, those visuals provide lots of support!

Deep in the Forest, by Brinton Turkle, is a clever variation on Goldilocks and the Three Bears. Teachers could easily pair this with a favorite version of Goldilocks to work on Anchor Standard 9 of the CCSS (Analyze how two or more texts address similar themes or topics in order to build knowledge or to compare the approaches the authors take.)

A Ball for Daisy, by Chris Raschka is this year’s Caldecott Medal winner. Again, students will easily identify with this story of a dog and her ball. Daisy’s expressions are filled with emotion, making these illustrations perfect for introducing inferring.

This is in no way a complete list, just my favorites. I’d love to hear about yours!