Earlier this month, I attended the TCRWP’s Saturday Reunion in New York City. One of the sessions I went to was “To Lift the Level of Writing, We Need to Lift the Level of Rehearsal and Revision: Mentor Texts Can Teach Not Just Qualities of Good Writing, But Process,” presented by Brooke Geller. The session began with Geller stating that kids need to see the big picture before they begin writing. Knowing what the finished product will look like is the first step in engagement. Geller described the following process to immerse students in the genre being studied, in this case, a research-based argument essay.

Unpacking a Text

- could be a published text, student work, or your own writing.

- students should spend time with the text, reading and rereading

- ask “What are you noticing?”

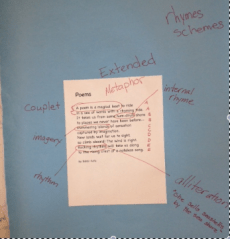

- put kids in groups of 3-4, give them a piece of writing in the middle of a big sheet of paper

- have them mark up the text with their observations and the evidence

- students should use their prior knowledge about genre– “What do you know about essays?”

- read first, then read with the eyes of a writer

- teacher should go from group to group and add her own thoughts

- come back together–create list of what they think are characteristics of the genre

- charts can be used as teaching tools

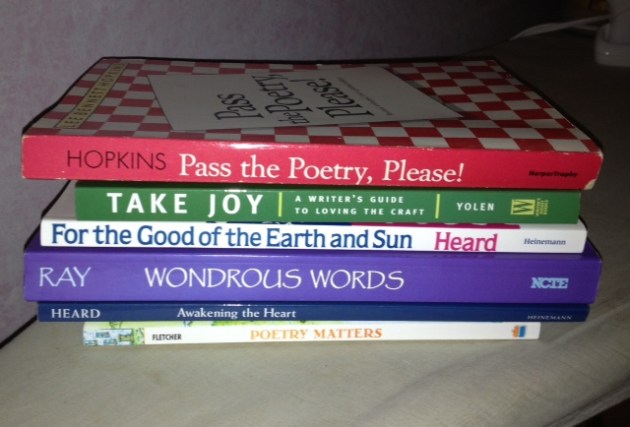

At my school, the fifth grade teachers were getting reading to begin a unit on poetry. We’ve been talking about ways to increase student engagement and the quality of their writing, and I suggested that unpacking poems would be a great way to begin.

The teachers and I selected five poems and mounted them on sheets of butcher paper. At the start of class the next day, the classroom teacher and I modeled the process for the students. We discussed the importance of reading the poem aloud and rereading it several times. Then gave each group their poem and a marker. As they began working, the room was filled with the hum of their reading. The classroom teacher and I moved from group to group, talking and rereading along with the kids. Certain poetic elements were easier to spot; the poem either rhymed or it didn’t. Some students could describe what they noticed, but didn’t know what it was called. It occurred to me that this activity was also an excellent form of pre-assessment. The teachers and I had a concrete list of what the students knew about poetry.

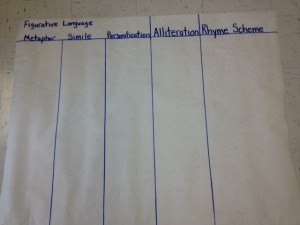

After school, the classroom teacher and I created this chart to use throughout the unit.

As students find examples of these poetic elements, they will be added to the appropriate column. These examples will support them when they begin writing their own poems. We will also add columns to the chart as we teach more poetic elements and devices.

A variation on this process suggested by Geller would be to put the same piece of writing on sheets of paper, but have a different focus question on each sheet.

Possible questions include:

- What makes this text (poetry, essay, etc)?

- How is this text set up? Why is this important?

- What is the purpose? How do you know this?

- How does the author show the heart of the story?

Students could rotate around room, rereading the text in light of each question.

As we reflected on the work of our students, we noticed that engagement had been high and all students participated in the discussions. We also noted that no one had mentioned anything about repetition of words, or the word choices the poets made. And while most students could spot a simile, metaphors were more difficult. Over the next few weeks, we will be crafting mini-lessons to teach these elements. We will continue to use the wonderful ideas Brooke Geller shared at TCRWP throughout the unit. I’ll let you know how it goes.

Thank you to Stacey and Ruth at Two Writing Teachers for hosting this Slice of Life Challenge!