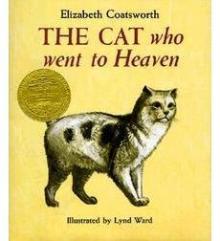

Last weekend Newtown’s C.H. Booth Library held their annual book sale. This sale is well-stocked, well-organized, and never disappoints. I always find a treasure or two, as well as more standard fare to restock our classroom libraries. One purchase I was especially pleased with this year was a paperback copy of The Cat Who Went to Heaven for fifty cents. This 1931 Newbery Medal winner by Elizabeth Coatsworth is a gem of a book. Many, if not all, of the CCSS literature standards could be addressed through a shared reading of this book. Certain passages are ideal for close reading.

The Cat Who Went to Heaven is an excellent example of a complex text, a text that Fisher, Frey, and Lapp describe as one that “often require[s] the reader’s attention and invite[s] the reader back to think more deeply about the meaning of the text.” (Text Complexity: Raising Rigor in Reading, IRA, 2012, p. 106) Shared reading of this story will help students develop the skills necessary to “readily undertake the close, attentive reading that is at the heart of understanding and enjoying complex works of literature,” a stated goal of the CCSS.

The story of a poor Japanese artist, The Cat Who Went to Heaven begins when the artist’s housekeeper returns from the market with a cat instead of dinner. The artist is furious that she has spent his precious pennies on a “goblin…[who will] suck our blood at night!” The housekeeper convinces him that “there are many good cats, too.” The artist relents, and the cat, whom they name “Good Fortune,” becomes part of their household.

Soon, fortune does indeed smile on the artist, for he is asked by the local temple to paint a mural of the death of the Buddha. The rest of the story unfolds as a series of events in the Buddha’s life, each one revealing an important aspect of his character and the personal qualities at the heart of Buddhism.

This structure makes this book an ideal choice for meeting standard RL.6.3: “Describe how a particular story’s or drama’s plot unfolds in a series of episodes as well as how the characters respond or change as the plot moves toward a resolution.” The theme of the story is also well developed and students will be able to explain “how it is conveyed through particular details” (RL.6.2) These elements, along with Coatsworth’s rich use of vocabulary, should generate many thought-provoking questions and discussions.

I will share this book with my sixth grade colleagues, as China and Buddhism are part of the sixth grade social studies curriculum. The depiction of the beliefs and practices of Buddhism are conveyed throughout this story and would reinforce the social studies content.

Jazz vocalist and composer Nancy Harrow has adapted this book as a series of 16 songs, which are available on CD. These have been performed as classic Japanese puppet theater. Although I couldn’t find a full performance of the puppet theater, you can watch a short scene here:

An interview with Harrow, in which she describes the process of writing the songs, can be seen here:

Sharing Harrow’s work with students after reading The Cat Who Went to Heaven would also allow students to work on standard RL.6.7: “Compare and contrast the experience of reading a story, drama, or poem to listening to or viewing an audio, video or live version of the text, including contrasting what they ‘see’ and ‘hear’ when reading the text to what they perceive when they listen or watch.”

Teachers around the country are concerned about having the materials needed to meet the demands of the CCSS. Rather than spending money on new materials, many of questionable quality, we should invest in time to revisit materials we already have but may not be using to full advantage. The Cat Who Went to Heaven is the perfect example of just such a book.

Be sure to visit Jen at Teach Mentor Texts and Kellee at Unleashing Readers to find out what other people have been reading lately. Thanks, Jen and Kellee, for hosting!