I discovered Rebecca Solnit many years ago when I spotted her book, Wanderlust: A History of Walking on a shelf at my local library. As a passionate walker, I was intrigued, and Solnit’s expansive perambulation from ancient Athens to today’s suburban sidewalks and treadmills didn’t disappoint. Kathryn Aalto describes Solnit as “a writer, historian, and activist who links ideas and places like string to thumbtacks.” (p. 161)

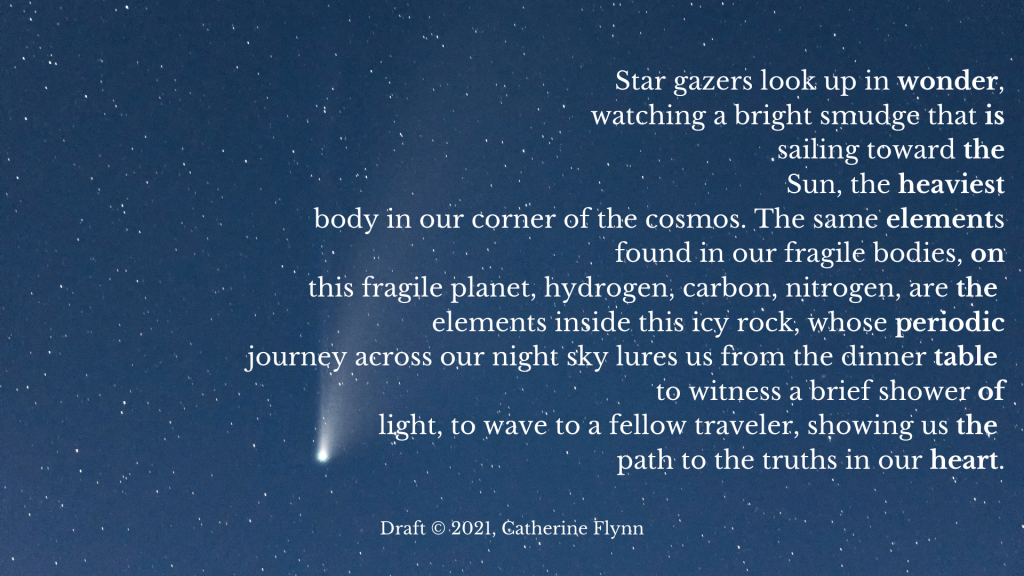

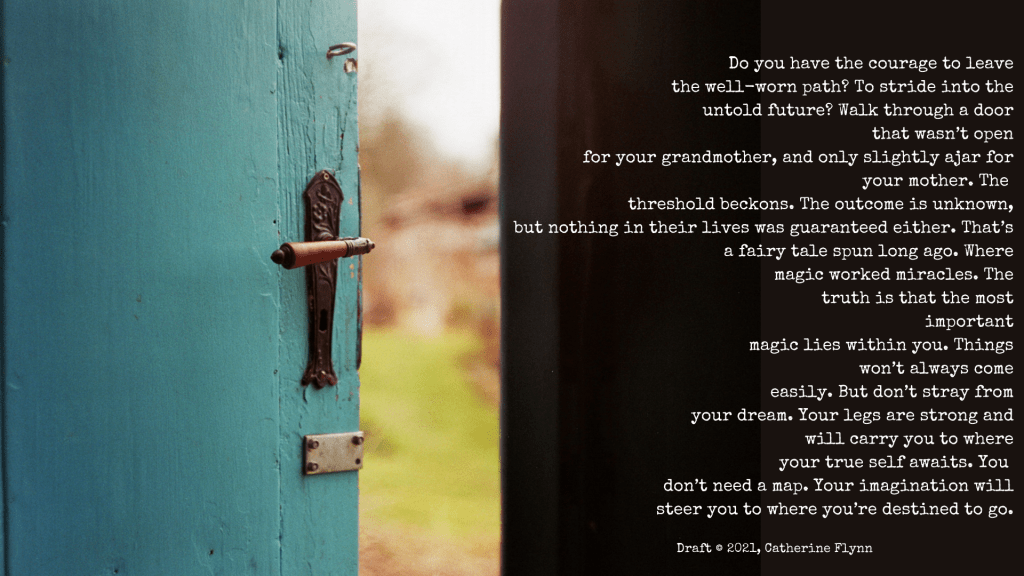

Because walking is what drew me to Rebecca Solnit’s work in the first place, I expected to write a poem about my daily walks, and thought a Golden Shovel would be a good form. My plan took a few detours. To begin with, I couldn’t find a quote I liked well enough to use as a strike line in Wanderlust. Searching through Solnit’s many other works, I found one I liked, but it was long. So I shortened it. (I have no idea if this is allowed, but I did it anyway.) Here is the original quote from A Field Guide to Getting Lost.

Leave the door open for the unknown, the door into the dark. That’s where the most important things come from, where you yourself came from, and where you will go.

Finally, this poem took an unexpected turn away from walks through my neighborhood and into a semi-autobiographical realm that was influenced by the fifteen writers highlighted in my previous Writing Wild posts. Writing is full of surprises!

Please be sure to visit Jama Rattigan at Jama’s Alphabet Soup for the Poetry Friday Roundup. You can also read previous Writing Wild posts if you’d like to learn more about some amazing writers.

Day 1: Dorothy Wordsworth

Day 2: Susan Fenimore Cooper

Day 3: Gene Stratton-Porter

Day 4: Mary Austin

Day 5: Vita Sackville-West

Day 6: Nan Shepherd

Day 7: Rachel Carson

Day 8: Mary Oliver

Day 9: Carolyn Merchant

Day 10: Annie Dillard

Day 11: Gretel Ehrlich

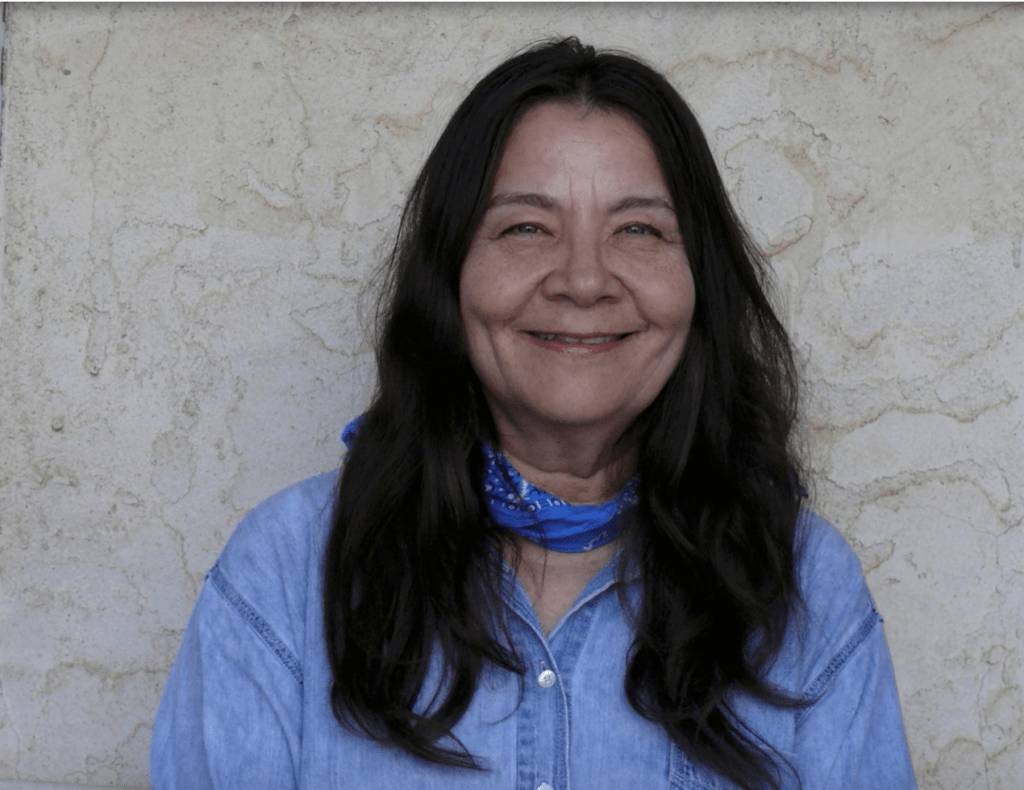

Day 12: Leslie Marmon Silko

Day 13: Diane Ackerman

Day 14: Robin Wall Kimmerer

Day 15: Lauret Savoy