Nowadays, it seems that Labor Day is more about the last official summer holiday and sales, not about the workers it honors. So today it seems appropriate to share books about the everyday heroes who took tremendous risks and made many sacrifices to help shape the labor laws we have today.

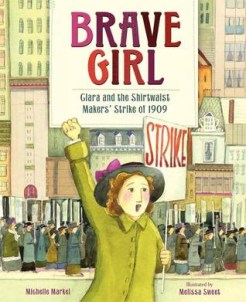

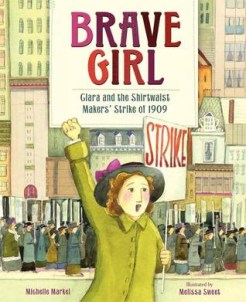

Brave Girl: Clara and the Shirtwaist Maker’s Strike of 1909, by Michelle Markel (Blazer + Bray, 2013; illustrated by Melissa Sweet) tells the true story of Clara Lemlich, who immigrated with her family from the Ukraine when she was 17 years old. Her father was unable to find work, so Clara went to work in one of the many shirtwaist factories on the lower east side of Manhattan in the early 20th century. Clara soon discovers the harsh realities of the garment industry, and helps organize the famous 1909 strike.

Melissa Sweet’s illustrations are always appealing, and here they provide a glimpse into the conditions of the tenements and factories of the time. Using her signature collage, Sweet incorporates fabric, stitching, and patterns to recreate Clara’s world. In an interview with Julie Danielson at Seven Impossible Things Before Breakfast, Sweet explains that this “felt like a fitting way to honor these brave seamstresses.”

The picture book format of Brave Girl shouldn’t discourage teachers of upper elementary grades from sharing this book with their students. In fact, Markel’s text is an ideal introduction to this important chapter of our history. Once students’ curiosity has been piqued, there are many other excellent books available to extend their learning.

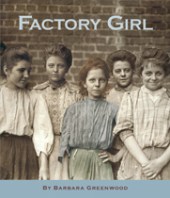

In Factory Girl, by Barbara Greenwood (Kids Can Press, 2007), combines fiction and non-fiction to bring the world of the garment and textile mills of New York and New England at the turn of the 20th century to life. Archival photos, many by Lewis Hine, reveal the terrible working conditions these children endured. This book also includes a timeline of the labor movement in the United States.

Katherine Patterson has written two novels that vividly depict the experience of young workers in New England textile mills. Lyddie (Dutton, 1991) takes place much earlier than the events in Factory Girl, but the situation is very similar. Lyddie arrives at a textile mill in Lowell, Massachusetts in the 1840s, just as several of the women are organizing to demand 10-hour working days. Patterson expertly weaves other aspects of life for these “factory girls” into the story. Facts like the “company” requirement of regular church attendance and the numerous restrictions on the girls’ after-work activities will be sure to provoke many heated discussions and are natural springboards for opinion and argument writing.

Bread and Roses, Too (Clarion Books, 2006) takes place in Lawrence, Massachusetts during the Bread and Roses strike of 1912. Sadly, the mill workers in this novel are still confronted with many of the issues Lyddie struggles against over half a century before.

As is often the case, it took a tragedy before these conditions changed in any meaningful way. The 1911 fire at the Triangle Waist Company led to the deaths of 146 workers who were locked into the factory so they couldn’t leave early. Albert Marin has written a riveting account of the tragedy in Flesh and Blood So Cheap: The Triangle Fire and Its Legacy (Alfred A. Knopf, 2011). Marin sets the stage by telling the story of why so many Europeans were desperate to come to America in the first place. Incorporating archival photos and eyewitness accounts, this book is an important resource for students and teachers alike.

While children in the United States today are protected by child labor laws thanks to the efforts of Clara Lemlich and countless others, the same cannot be said for children around the world. These books open the door for students to conduct research and gain new insights into child labor around the world. The New York Times Learning Network has a lesson plan and resources related to the factory collapse in Pakistan earlier this year, and Teachers College Reading and Writing Project has an extensive collection of links to articles and videos available on-line, as well as books that address both the history of child labor and examples of child labor as it exists today.

There are many other fine books about other leaders of the Labor Movement, as well as fictional accounts of its many unsung heroes. I’d love to know which books are your favorites.

Be sure to visit Jen at Teach Mentor Texts and Kellee at Unleashing Readers to find out what other people have been reading lately. Thanks, Jen and Kellee, for hosting!