If you have been following these Writing Wild posts, you may have noticed the profiled authors are in roughly chronological order. As we approach the present, there are more writers I am familiar with, even a fan of. That is true today. Award-winning poet Mary Oliver, who died in 2019, is well known and widely loved. Ruth Franklin, writing in The New Yorker, states that Oliver “tends to use nature as a springboard to the sacred.” Kathryn Aalto explains that “a fusion of mystery,prayer, and presence is at the heart of all Oliver’s poetry and prose.” (Writing Wild, p. 92)

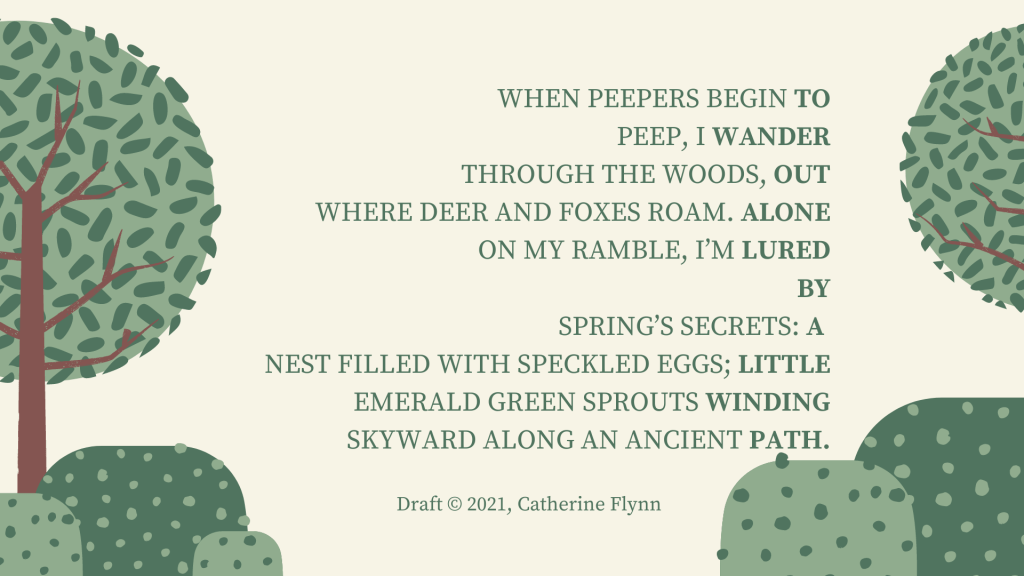

Attempting to write a poem after Mary Oliver seems like a fool’s errand. And yet I am compelled to follow her “Instructions for living a life: Pay attention. Be astonished. Tell about it.” I have been following these directions for over sixty years, long before I’d heard of Mary Oliver. But the poetry of those steps has always been in my bones.

I decided the best approach to today’s challenge would be to use one of Oliver’s poems as a mentor text, copy it “word for word, then replace [that poet’s] language with your own.” (I posed this challenge for my critique group back in February.

Deciding on a subject wasn’t difficult. Also on my blog today is a celebration of Leslie Bulion & Robert Meganck’s wonderful new book, Spi-Ku: A Clutter of Short Verse on Eight Legs. I have always loved the beauty and grace of spiders. A spider I observed in my garden one morning became the topic of this poem. I couldn’t find and poems by Mary Oliver about spiders (I looked quickly; there must be one or two). The mentor poem I chose is “The Instant” (found on p. 51 of Devotions: The Selected Poems of Mary Oliver). Oliver’s words from the original poem are italicized.

The Instant

after Mary Oliver

Today,

a small spider,

pearly and round

scrambled through

the high grass, it

seemed desperate to

get away from

my invading hands

but couldn’t move

fast enough. Was she

swollen with eggs,

impelled by instinct

to protect them?

My heart ached for her,

remembered a feverish boy,

clutched by a silent enemy

one long ago night, and with no sound at all

I was gone.

Draft, ©2021, Catherine Flynn

Previous Writing Wild posts:

Day 1: Dorothy Wordsworth

Day 2: Susan Fenimore Cooper

Day 3: Gene Stratton-Porter

Day 4: Mary Austin

Day 5: Vita Sackville-West

Day 6: Nan Shepherd

Day 7: Rachel Carson